By Ryan Sayre

I really can’t think of a better example of what we might call an anthropological ethos of urgency than a

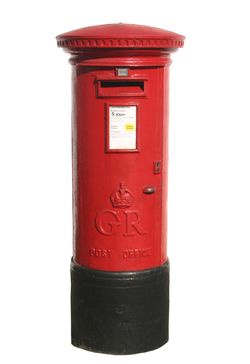

roadside postbox in the time of war. During the OAS terrorist campaigns in Algeria in the 1960s, a foreign journalist turns to a colleague with this story:

“I remember asking another Japanese reporter how he managed to file his stories. “I send many by post,“ he said. “Mine are not urgent news stories.“ As he talked, he pointed to a letterbox outside the Aletti Hotel, which, he told me, he always used. A sticker, in French, on the box, read: “Do not post letters here. Owing to the circumstances, collections have been discontinued since February 12.“ We were in May.

The anthropologist offering this anecdote gives it as a brief interlude of humor, a gentle ribbing of the journalistic field, a little snatch of good-humored racism. I wonder, however, whether, just for shits and giggles, we might hold our laughter for a moment and try taking the Japanese reporter at his word? What I mean is, let's just assume for a moment that he means what he says about the non-urgency of his dispatches. Let’s assume he parles French like a Bonaparte, has a semiotician’s eye for signage, and makes use of this out-of-service postbox for no reason other than that it strikes him as the most suitable place to store observations on a situation too liquid to be touched in the immediate present. The postbox in which our reporter stuffs his dispatches is a kind of time capsule, yes, but rather than the tin boxes we buried as children that wait idly for the arrival of some pre-established future date, these dispatches are attentively listening, devoting themselves to the moment when the ping of empty copper shell casings gives over to the jingle of a mailman’s steel keyring.

… More here.